The plague surrounds us more and more and with its tentacles overpowers the possibility of normal functioning and work. It is getting stuffy, more and more stuffy… Artists are also among those affected by this paralysis. Cultural institutions were closed, events were canceled. And an important aspect of their functioning is also foreign travel. Freelancers work not only in their own country. But planes have been grounded at the airports and borders have been closed. The prospect of international action has been shattered.

It turns out, however, that not all plans of this kind must fall for nothing. Some of them can be saved. Let me give you an example of a decision taken by organizers of the the European-funded “Memory of Water” project. There was a problem of how not to lose a possibility of producing works by artists in Govan, Scotland. Initially, it was discussed to postpone them to the next year. However, in the face of the ensuing financial difficulties, there was a question whether all the institutions – partners in the project would survive for so long. Finally, it was decided that previously prepared projects would be carried out by local artists. Today I want to trace the effectiveness of this recipe for action with the help of a delegated „avatar”.

The Gdańsk community is represented in „Memory of Water” by Iwona Zając, invited by the Baltic Sea Cultural Centre. Much of her work is closely related to the former Gdańsk Shipyard. She had a studio there for sixteen years, which gave her a deep insight into problems of this workplace. Thanks to this, she could record conversations with local workers. The collected materials were used by her in 2004 to create a mural entitled „Shipyard”. On a wall separating this industrial area from the rest of the city, she placed fragments of the obtained confidences. They concerned the shipyard workers’ relationship with this place, their fears, needs and hopes.

In Scotland, when she was to choose a place to carry out her creative intervention, she decided to go to the post-shipyard areas. Since the nineteenth century, Glasgow (of which Govan is part) has been one of the main European shipbuilding centres. This fact was the source of the city’s prosperity. It was also an extremely important building block of local identity. However, as the world shifted to a global economy, it became more profitable to move large-scale production outside the European continent. When the British government refused to grant a loan to the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders consortium of five local shipyards (Fairfield’s, Stephens, Connel’s, Yarrow’s and John Brown’s) in the early 1970s, these plants were closed. Tens of thousands of people lost not only their jobs but also their meaning in life. As a result, a huge social movement called „work-in” was born. Shipbuilders went on strike and protests, but what they wanted most was to continue building ships and defend employment. That is why trade unions led by Jimmy Reid and Jimmy Airlie mobilized the whole country to support their action. Thanks to donations, hundreds of jobs were temporarily saved. In February 1972 the government agreed to keep the Yarrow Scotstoun yard and the Fairfield in Govan, but they were no longer competitive in the world market. However, a large part of the generation of workers who built ships from their grandfather’s great-grandfather left. This story is like that of the Polish coast.

Agnieszka Wołodzko: Let us start from the beginning. Tell me what happened when it turned out that you will not go for this artist-in-residence?

Iwona Zając: First, there was a series of meetings at Zoom. We discussed whether to do it or postpone it to the future. The first idea was to move it to next year, because the focus of this project is working with communities and being there, as well as the value of our meetings – of artists participating in „Memory of Water”. During our earlier residencies – in Levadia and Gdańsk – we accompanied and participated in our projects. It will not succeed, and we have not managed to recreate it from a distance, and we were also sorry. However, it should be remembered that the institutions that invited us faced a new problem, because they do not know what their situation will look like next year, or whether they will still exist.

A.W.: Then it was decided that your work would be done by artists from Govan.

I.Z.: Yes. We knew that we had to prepare it in such a way that it could be produced on the spot. It was also especially important to us that the artists cooperating with us were paid a fee. That the money that were meant for our journey and accommodation in Govan would go to them.

A.W.: But have you been to Govan before?

I.Z.: Yes, we were there in September 2019. We spent a week there for research and meeting people.

A.W .: And then you saw and chose the place of your future work? It was one of the dry docks.

I.Z.: Yes. I knew immediately what I wanted to do. I feel natural in such places. When I got there, I felt them right away. I did not need anything more to be happy there. I realized that I wanted to work there.

A.W.: Can you enter this area?

.Z.: No, the dry dock I have chosen can only be seen from above, from the bus stop or illegally entered. The gate is ajar, and inhabitants are getting there. Nobody is watching it. But to be able to implement my project, we had to obtain a consent of the owner of this area, because it is in private hands.

A.W.: What was your idea for this place?

I.Z.: I have prepared one inscription taken from the local context, which I have broken into two parts. They were to be painted on the walls of the dock descent.

A.W.: How did you choose them?

I.Z.: I was incredibly lucky to find this sentence. During an earlier stay in Govan we saw these docks while walking along the waterfront. Our guide was Iain McGillivrary – a founder and executive director of the Clyde Docks Preservation Initiative. He guided us along the „Walk to the Docks” route and told a story of an eight-year campaign to save the iconic Graving Docks Govan and the successful overturning of a plan to build 750 high rise flats on this site. I liked this place right away, but we did not have time for a longer exploration, so on the last day of my stay, in the morning I went there alone. I wanted to do documentation, check what the area looks like up close and from a perspective of a bus stop. I was interested in the descents, stairs to the dry dock. I liked its design, it looked like a finished installation. Then I went to the Fairfield Heritage Center. I spent a few hours there to listen to recordings of, among others, interviews with shipbuilders. I was walking like on a string.

I was very keen on extracting something that would be recognizable and closely related to this place. I was contacted by James Craig, who had previously worked for fifteen years in the Govan shipyard. He also acted as a local storyteller and then was the chief manager of shipyards around the world and is somehow affiliated with the Fairfield Heritage Center. I asked him to choose sentences from these interviews. I sent him a link to my website where I have recordings with Gdańsk shipyard workers. I told him that I wanted passages where the shipbuiders talked about life or about their relationship with the shipyard. And James sent me some sentences. In addition, I also had a contact with the Center’s coordinator – Abigail Morris, from whom I had to obtain a license to use them.

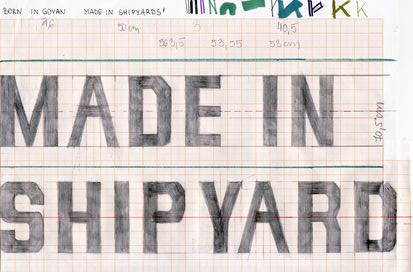

A.W.: The sentence you have chosen is: „Born in Govan, made in the Shipyards”. How do you translate it?

I.Z.: I do not translate it at all, I just feel it. I knew it could not be overdone. It must be eye-catching, identical with this place and legible to the inhabitants. It was also important to me that graffiti artists work there, so entering them with your vision and painting over their works – you also need a reason for that.

In general, all the slogans James chose for me are ready-made advertising slogans for Govan. They have power. I wanted to make T-shirts with patterns printed on them, but it was too much work for me. But James took an interest in it. He found it cool and prepared T-shirts like that. Now he is working to be able to sell them in the Center.

A.W.: So, it looks like they carried your idea further.

I.Z.: Yes. This is the most important thing for me. It has not been my goal to make some big, spectacular objects, but to bite into the place as much as possible and create something that is not alien. You could say it is nothing special – a writing on the wall. But for me, to get into the process, to make it happen, is a couple of months of work, if not more.

A.W.: How did your cooperation with local artists work? To what extent were they just contractors of projects that you had fully defined, and to what extent did they have some creative input? Have they somehow advised you, guided you to some tropes?

I.Z.: I cannot speak on behalf of others. I do not know what the case with them was. I was lucky that Beatrice Searle was invited to collaborate. She has a studio next to Govan Graving Docks, on land once owned by the shipyard. While walking with Iain, we were able to visit her. We saw what she creates and what tools he uses. She works in stone and with letters. If it were not for her, I would have used a stencil. I would cut it out and send it. Because we were asked to prepare our projects in an easy way for people from Govan. Keep in mind that they too have had a lockdown and are currently getting ready for a second closure.

A.W.: Who else did you work with?

I.Z.: First, I wanted to work with Glasgow Press, a printing house located next to Beatrice’s studio. I was interested in the fact that it has been operating in Govan for generations and that they use the old printing technique and have fonts characteristic of this place. Unfortunately, they did not reply to emails, so I started looking for another way. Due to the fact that at the Fairfield Heritage Center I had compiled exhaustive documentation of the things, documents and posters that caught my attention, I started to search for more information on the Internet on my own. For example, I was interested in videos and articles about the strikes and demonstrations in the shipyards in Govan in the 1970s and concerned the grassroots movement known as the ‚work-in’. I am from Gdańsk and I am familiar with this fight for employee rights. My attention was drawn to posters that people were carrying at demonstrations, or that they had hung on the walls during deliberations to save the shipyards. And because the letters were often hand-painted, they were of their nature.

I knew that a challenge like a perspective awaited me, because you cannot enter the Graving Docks legally and you cannot see it up close. Only from the perspective of the road that is above and from the bus stop. And it is at an angle to the dock descent. So, I realized that I had to do something that would visually attract attention from this distance and would fit into the character of this place. To do this, I went to a lettering workshop in February, run by Eugenia Tynna (an assistant at the Faculty of Graphics of the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk) at the City Culture Institute. And there, Eugenia said, among other things, that the font has time written in it, which immediately allows us to read that it belongs to this newspaper, or until a specific time, e.g. in the nineties. She also said that if we grow up with a font, it becomes natural for us and easy to read, although for others it may be completely incomprehensible. It is part of our identity. And this was what I followed. After this workshop, I invited Eugenia to cooperate. She also told me a technique for doing my job. „Przyprócha” is an old method of transferring letters. A perforation is made on a printout or a drawing, and an inscription is copied onto another surface using a pad of charcoal or chalk.

It mattered to me that Beatrice would fill in the writing with her own hands. That it would not be a print from a stencil, but her body, she, her skills. And all this, of course, I consulted with her. We had a meeting at Zoom, and we wrote e-mails to each other.

A.W.: What kind of typography did you use after all?

I.Z.: Hand-painted letters from UCS (Upper Clyde Shipbuilders) posters. Eugenia said that this is a kind of so-called „dirty letters”. Together with Hamish Rhodes and Inês Cavaco (working on „Memory of Water” for Fablevision Studios), we checked what kind of font these letters were. And we found: Liquorstore Bold, Epsum Bold and Lobby Card Oblique. On their basis and based on the posters, I designed my own font. It was not to make it looks too professional. I wanted to introduce a little dirt and a bit of what normally should not happen in graphic design. Then Eugenia took up my project again, who developed it in a graphic program.

A.W.: Has anyone else helped you with this realization?

I.Z.: Just mentioned Hamish Rhodes and Inês Cavaco, as well as a researcher Ian McCracken and Liz Gardiner from Fablevision Sudios. While working on the production, Hamish emphasized that these are historical places. The docks are of partially hand-carved gray granite, which is unique in Scotland and belong to the highest category of protection for historic sites and buildings. I was anxious not to use materials that would damage it. Therefore, we first thought of a washable spray, and then the „crew” from Govan bought ecological paints. We do not cover the background on the inside. This is a game with what is inside and what is outside. The outside facade will be repainted and what is inside remains as it is, with all these layers. So, the letters were put on a natural base, consisting of the structure itself, the graffiti covering it and nature, which also changed the look of this wall. Inside, there is the slogan „Born in Govan”, and outside – the wall is covered with gray paint and the inscription „Made in Shipyards” painted. Because the structure and the distance allow for a play with perspective, the two inscriptions overlap.

A.W.: Has not the project been implemented yet?

I.Z.: Not yet, because the weather interrupted. It is raining. I think it is a matter of the next few days.

As the example above shows, the objective difficulties in realization the artist’s plans led to a creative reformulation of her original intentions. In their place, an alternative method of work necessarily emerged. Delegating other people to carry out the project did not cause them to passively replicate what she was unable to do. Thanks to the establishment of a local working group, whose members were partners and creatively involved in the intended implementation, Iwona did not cooperate with passive „avatars” but achieved a new quality, not only artistic.

Zrealizowano ze środków Miasta Gdańska w ramach Stypendium Kulturalnego.